The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the demand for and consumption of single-use plastics. There is a growing concern over the unprecedented increase in medical plastic products, including gloves, protective medical suits, masks, hand sanitizer bottles, takeout plastics, food and polyethylene goods packages, and medical test kits since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The management of waste originating from SUPs has become a troubling issue during and coming out of the pandemic (Benson et al., 2021; Vanapalli et al., 2021).

As of September 2022, about 617 million people worldwide have been infected with the COVID-19 virus (Americas: 28.76%; Asia: 30.44%; and Europe: 36.4%) (PAHO, 2022; WHO, 2022a & 2022b). In most countries, governments issued lockdown directives, as well as social and physical distancing measures to prevent or reduce the spread of COVID-19 virus. Plastic products have played important roles in protecting individuals globally to prevent infection since 2020.

Governments adopted strategies to prevent the spread of COVID-19 virus. For instance, health workers are required not to reuse their personal protective materials. As a result, tons of plastic medical waste are discarded daily worldwide. Further, the World Health Organization (WHO), the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control have recommended physical distancing and use of protective materials by their population. Therefore, in line with these recommendations, millions of pieces of personal protective equipment (PPE) and plastic materials have been produced and discarded daily (Benson, Bassey, & Palanisami, 2021).

The range of personal protective equipment (PPE) used by heath workers and the public includes masks, gloves, protective aprons, face shields, safety glasses, sanitizer bottles, plastic shoes, and medical gowns, which are mostly made from non-woven materials including polymeric substances such as polypropylene. Gloves are made from several materials such as chloroethene polymers, neoprene, and vinyl, which are not biodegradable. These plastic products are categorized as macro- and meso-plastics and can enter the environment through poor waste management or improper discharge into the marine and terrestrial ecosystems (Jeyasanta et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was also an increased demand for single-use plastics in general, which added on an already out-of-control global plastic waste problem. While the numbers are large, the magnitude of this mismanaged plastic waste is unknown (Peng, Wu, & Zhang, 2021). To keep up with the large demand for personal protective equipment (i.e., face masks, gloves, aprons, bottle of sanitizers, protective gears, and face shields), many single-use plastic (SUP) legislations have been withdrawn or postponed (Parashar & Hait, 2021). Further, lockdowns, social distancing, and restrictions on public gathering increased the dependency on online shopping at an unprecedented speed, leading to the production and distribution of a lot of packaging material made primarily of plastics (Asian Development Bank, 2020; Thakur, 2021).

The Pandemic and SUPs Pollution

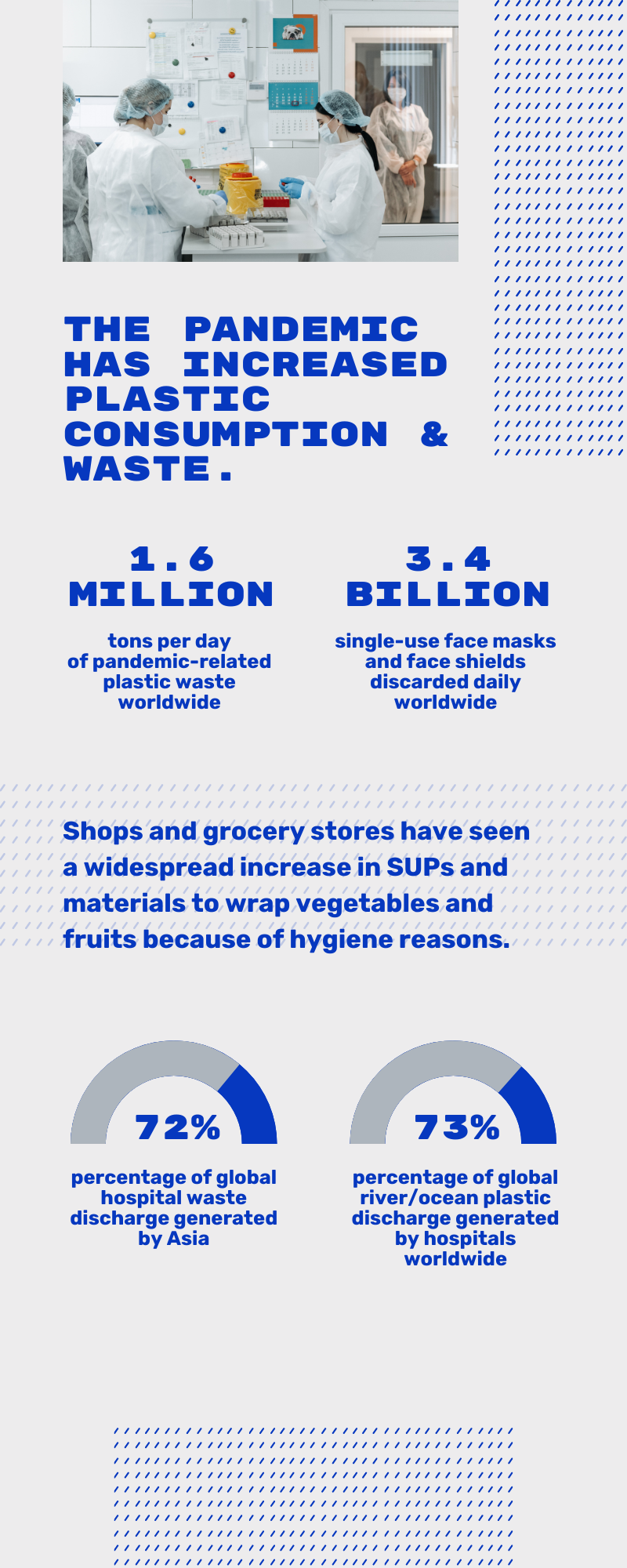

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the plastic pollution problem through consumers's need for SUPs and materials for health and safety reasons (Parashar & Hait, 2021). COVID-19 has increased the demand for SUPs, escalating the amount of consumption of the already out-of-control discarded plastic. Shops and grocery stores have seen a widespread increase in SUPs and materials to wrap vegetables and fruits because of hygiene reasons (Benson, Bassey, & Palanisami, 2021).

The amount of SUPs consumption led to an increase in environmental pollution. For instance, terrestrial environmental plastic pollution is the main source for marine plastic debris, which originate from anthropogenic emissions. To summarize, plastic waste harms the terrestrial, riverine, and marine (ocean) environments. Over the years, the global ocean, seas, and coastal environments have been directly and indirectly riddled with billions of tons of plastic marine debris produced from human-mediated activities (Fred-Ahmadu et al., 2020a; Nghiem et al., 2020). Plastics from oceans can come from both land-based or marine sources. They are classified as: (a) nanoplastics (size range between 1-100 nm); (b) microplastics (size range between 1um-5 mm); (c) mesoplastics (size range between 2.5 cm-5 mm); and (d) macroplastics (size range above 2.5 cm) (Benson & Fred-Ahmadu, 2020; Fred-Ahmadu et al., 2020b; Jeyasanta et al., 2020).

The amount of pandemic-associated plastic waste generated worldwide since the outbreak is estimated at 1.6 million tons per day. This waste is seen littering the streets, roads, parking lots, dumpsites, gutters, shopping carts, medical facilities, and entering ocean and affecting the environment as a whole (Benson, Bassey, & Palanisami, 2021). Specifically, it causes a surge in plastics washing up the ocean coastlines, beaches, and littering the seabed. Most of the plastic is from medical waste generated by hospitals, but it adds individual SUP such as personal protection materials and online-shopping packaging material. This poses a long-lasting issue for the environment and ocean (accumulation of waste on beaches and coastlines) (Nzediegwu & Chang, 2020; Peng, Wu, Schartup, & Zhang, 2021; Syam, 2020).

It is estimated that 3.4 billion single-use face masks/face shields are discarded daily as a result of COVID-19 pandemic, globally. Experts state that data analysis indicate that the pandemic will reverse the long years of global battle to reduce plastic waste pollution (Benson, Bassey, & Palanisami, 2021). Approximately 3.8 thousand tons were released into the global ocean, representing 1.5 of the global total riverine/ocean plastic discharge. Hospital waste represents 73% of the most global discharge worldwide, and the most of the global discharge is from Asia (72%) (Peng, Wu, Schartup, & Zhang, 2021).

Treatment of plastic waste is not keeping up with the increased demand for plastic products. Pandemic epicenters in particular are having a hard time managing and processing the waste, and not all the used SUPs and packaging materials are handled properly or recycled (Picheta, 2020; UNCTAD, 2020). The mismanaged plastic waste is consequently discharged into the environment and ocean. Lately, research has raised the present and potential future problems of COVID-19 plastic pollution and its impact on the environment and oceans (De-la-Torre, & Aragaw, 2021; Canning-Clode, Sepulveda, Almeida, & Monterio, 2020; Thiel et al, 2021).

Environmental impact of personal protective equipment (biomedical plastic waste)

Land-based anthropogenic activities (i.e., disposal of biomedical wastes) are considered potential sources of toxic, infectious, and radioactive pollutants (WHO, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic has created more biomedical waste in the form of waste plastics. According to the WHO (2018), on average, about 0.2 and 0.5 kg/day of hazardous biomedical wastes are generated by low-income and high-income countries. China (the first country to report COVID-19), documented a 23% increase in the amount of biomedical plastic waste, meaning that the country has accumulated 142,000 tons of biomedical waste (Tang, 2020).

The discharge of plastics can be transported over long distances in the ocean, encounter marine wildlife, and potentially lead to injury and death. For instance, reports estimated that 1.56 million face masks entered the oceans in 2020 (Bondaroff, 2020). There are cases being reported of entanglement, entrapment, and ingestion of COVID-19 waste by marine organisms, leading to death (Gallo Neto et al., 2021; Hiemstra, Rambonnet, Gravendeel, & Schilthuizen, 2021). Additionally, the plastic debris could also facilitate species invasion and transport of contaminants, including the COVID-19 virus (Mol & Caldas, 2020). Given that COVID-19 is not over yet, the potential impacts or the total amount of pandemic-associated plastic waste and its environmental and health impacts are not known (Peng, Wu, Schartup, & Zhang, 2021).

Further, there is a growing concern that discarded surgical masks, medical gowns, face shields, safety glasses, protective aprons, sanitizer containers, plastic shoes, respirators, and gloves arising from the current COVID-19 pandemic could end up in the global aquatic ecosystems. They all are discarded in a plastic bag after use and then dumped in the trash (U.S. FDA, 2022). This is an unprecedented rise of disposable materials that contributes to the plethora of plastic pollution (Boyle, 2020). Although these protective measures for COVID-19 are necessary, they are worsening the plastic waste problem as more SUPs are added to the global environment and oceans, given that the personal protective equipment are not adequately recycled (Morford, 2020; U.S. FDA, 2022). Specifically, the COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate the existing plastic pollution challenges created by over 10 million tons of plastic that have been estimated to threaten the environment, global oceans, and the marine organisms (Kane et al., 2020).